A History of the Georgetown Loop

The history of the modern Georgetown area begins with the town’s namesake, George Griffith, in the summer of 1859. Drawn from their homes in Kansas by news of gold strikes in Idaho Springs / Central City area, George and his brother David headed west, only to have their hopes dashed like so many others that found all the good areas already claimed when they arrived. Moving up Clear Creek Canyon from the previous mining boomtowns, George happened across a rich vein of gold ore in the area of obviously what we now call Georgetown. Unfortunately, mining the the immediate Georgetown area didn’t pan out so well (no pun intended), but five years later and a few miles west, prospectors unearthed bountiful supplies of a metal almost as valuable in that day – silver. The place? Silver Plume, of course, officially incorporated in 1870.

With the new silver strikes occurring at a frantic pace, Georgetown quickly became the booming hub of the Argentine Mining District. Like all mining booms in early Colorado history, one of the core problems to be overcome was transportation of supplies in and ore out. The answer, as again with most early mining towns, was to try to attract a railroad. Tucked far up in fairly inhospitable terrain, Georgetown (at 8500 feet) would be difficult enough to reach by rail, but in 1869, the Colorado Central (under the control of Jay Gould’s Union Pacific, and under the direction of Edward Berthoud and William Loveland) began to build west out of Golden (the end of the standard gauge) through Clear Creek Canyon. Predating the start of the mighty Rio Grande system by a short time, the CC probably qualifies as one of Colorado’s first great experiments in three-foot gauge.

Even with grand backing and ambition, the railroad took nearly three years to get its first train into Blackhawk, CO, arriving in 1872. Blackhawk was the closest of the mining towns for the CC, and after connecting one and establishing a source of revenue, it began to look westward towards the Idaho Springs and Georgetown areas. Trackwork was completed to just outside Idaho Springs by 1873, and it would stay there for nearly four years due mainly to an economic downturn. Then, in June of 1877, with the backing of Union Pacific, the railroad finally started service into Idaho Springs proper. That left only 12 miles into Georgetown.

Business-savvy UP didn’t let the line languish at Idaho, knowing more freight potential lay immediately to the west. In only two months, the line was completed into Georgetown. However, the real traffic (mining-related) was still two miles further at Silver Plume. Silver Plume, however, was at 9100 feet and, as mentioned, only about 2 miles west – a grade of 6% from Georgetown, straight shot, far too steep for any significant main or branchline railroad. Oddly enough, it was not the Silver Plume traffic that eventually spurred construction.

In 1879, the large Leadville mining strikes were starting to occur, and UP, still under Gould, had the idea that they could be the first-mover in this new market. Their line at Georgetown could conceivably be extended west, under the Continental Divide near Loveland Pass, and then tap Leadville – probably via Dillon and then Independence Pass. Construction was begun immediately an an elaborate plan, dreamed up by UP Chief Engineer Jacob Blickenderfer, to connect Georgetown with Silver Plume.

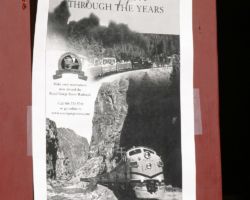

That elaborate scheme was a line twisting, winding, and looping over itself in Clear Creek Canyon – what today we know as the Georgetown Loop. This plan essentially amounted to winding some 4.5 miles of trackage into a 2 mile linear space, mainly by looping back over itself. This is what leads us to the centerpiece of the Georgetown Loop – the Devil’s Gate viaduct, a tall, curved, spindly iron trestle built over Clear Creek and the track below at a narrow point in the canyon (Devil’s Gate). The bridge is 95 feet off the creek below, and is some 300 feet long, forming an 18.5 degree curve. The bridge arrived in pieces in September of 1883, and was up by November of that same year. However, due to incorrect assembly (two bents were reversed) as well as substandard rivetting, the bridge wasn’t capable of service until February 1884.

In the process of building this ambitious extension, Union Pacific reorganized its narrow gauge system under a new name – the Georgetown, Breckenridge, and Leadville Railroad – and proceeded at once with survey and construction work. Even with the furious race to reach Leadville first, construction of the Loop took time. Due to various problems that are not fully understood, along with the significant construction problems with the bridge mentioned above, the first train didn’t reach Silver Plume until March of 1884. The line was extended as far west as modern-day Bakerville in mid-1884 when the news hit – General Palmer’s Rio Grande narrow gauge system was just about to tap Leadville, leaving UP’s GB&L as at best the second railroad into town, or more likely the third. The Rio Grande’s route, while longer (south from Leadville to Salida, then east along the Arkansas, through the Royal Gorge, and north from Pueblo to Denver) was nearly all water-level grade. Much straighter, fuel efficient, and faster than the GB&L ever could be, Palmer’s route was superior in most ways. Also, another narrow gauge railroad from Denver – the Denver, South Park, and Pacific – would reach Leadville in 1887 via the South Platte Canyon and South Park. With this news, the impetus for extending the GB&L was lost, and so was interest in the project. Bakerville would forever be the end of the GB&L system.

As things would come out, there was no reason to cross the Divide. In 1890, both the GB&L through Georgetown and the Denver, South Park, and Pacific line to Leadville (and beyond) would be merged together into the Union Pacific, Denver, and Gulf. Even that was a stopgap for these small, failing railroads, and by 1899, UP was out of the narrow gauge business in Colorado. Control of the entire system passed to the Colorado & Southern.

The idea of the tourist dollar was never lost on UP nor on the new owner, the C&S. Both used the Devil’s Gate bridge as a scenic cornerstone in advertising the line, and the C&S went as far as constructing tourist facilities in Silver Plume in the early 1900s, and connecting tramways provided an additional draw for tourists. While this succeeded for a while, by the late 1920s, passenger service was down to just a car or two on the regular mixed freight. The end of the route was closing in – by 30-Jan-1939, abandonment was official, and the line between Idaho Springs and Bakerville was ripped out that summer. Included in that was the scrapping of the original Devil’s Gate bridge in June of 1939, and was actually one of the last things pulled up. By 1941, the entire former GB&L/CC system was gone – clipped back to the end of the standard gauge at Golden, with the final train running 4-May-1941.

Today, much what was the CC grade between Golden, CO, and the fork between the Blackhawk and Georgetown lines (near the junction of US 6 and Colorado 119 today) is buried under US Highway 6, or was obliterated in the highway’s construction. Much of what existed between the fork and Georgetown is under I-70, buildings, or other side roads. The site of the proposed Continental Divide tunnel was very near what now is the Eisenhower Memorial Tunnel on I-70. Leadville’s mines are shut down, and it no longer has active rail service to the outside world (though a former C&S branch survives as the successful Leadville, Colorado & Southern tourist line). Everyone believed that the era of narrow gauge in the Clear Creek Canyon had passed into the archives of history, never to be revisited. However, I told you this was an odd little railroad…

The Colorado Historical Society and other interested parties began working to preserve the mining heritage of the Argentine District sometime in 1959, starting with the donation of some 100 acres around the site. Over the next decade, the CHS worked to acquire most of the old right-of-way and space necessary to rebuild the railroad. Finally, in 1972, five people (or at least the five that are often credited) – Lindsey and Rosa Ashby, Don Grace, Dick Huckeby and Dave Ropchan – started to seriously put together a plan to rebuild the line. By 1973, the two groups began working together, and the resources started to come together. UP, BN, and the Great Western all contributed materials to the project. The original Silver Plume depot was donated back to the Society and placed near its original location in south Silver Plume (Photo #2). The US Navy contributed labor, by way of training camps for their Mobile Construction Batallion (otherwise known as CBs, or SeaBees), who worked to install track and bridges. By 1975, the railroad had acquired various equipment and made its first revenue run down a mile and a half or so of track. In 1979, the line could go no further, having reached the south abutment of the chasm formerly spanned by the viaduct. At this point, it was time to figure out how to reconstruct the centerpiece of this line – the Loop bridge itself.

Thanks to hard work by individuals and the CHS, a million-dollar grant was made from the Boettcher Foundation for completing the line. Along with other grants, this gave just the funding needed to complete the loop project. In what has to be one of the oddest turns of events in narrow gauge railroading, the spectacular bridge was rebuilt true to the original (Photo #3) – started in June of 1983, and by 1-Jun-1984, the first train rolled across it. Within a few months, the railroad was complete to how it is today. This is the model on which the railroad is built – the property is owned by the Colorado Historical Society as part of their historic district, and the trains and operations are subcontracted out to another firm – the Georgetown Loop Railroad, a company put together by Mr. Ashby and his associates. Both parties have worked together since the beginning to make it the tremendous success it was. Remember that, it’s important in part 2.

The Current Mess (2004)

Note: I’m going to do a lot more editorializing here than I normally do. Normally trip reports stick to history and my experiences, but here I feel compelled to discuss the current mess the Loop is in, including the departure of the current operator. Much of this will paint the current Colorado Historical Society in a rather negative manner. I’ll both present facts that have shown up in local newspapers and the railfan press, as well as put my opinion on them. If anyone sees factual errors and can substantiate their claims, corrections will gladly be made and credited. However, my commentary on the situation is, while vitriolic in spots, supported by the facts I’ve seen, and it likely will not be swayed unless you can present some serious, independently-verifiable facts to the contrary. Remember, in the end, it’s my opinion. Everybody should make their own judgement based on all the facts of the situation they can find.

Note 2 (from 2020): With 16 years of hindsight now, it’s easy to see that many of the predictions were correct. Railstar’s first year was an astounding failure, partially due to its lack of equipment and experience, and partially due to CHS’s inept micro-management. Ridership was only 39% of the previous year. This went on for about four seasons until a local Georgetown businessman named Mark Greybill bought out Railstar’s contract in 2009 and put the Loop back on track. Today, in 2020, it’s once again a top notch operation with experienced people and appropriate equipment. Just think where we could have been if we didn’t have to go through 16 years of rebuilding.

While riding the 1210h train, our brakeman Ryan (at least I think this is Ryan, seen here doing a little recording of his own in Photo #4) announced as part of his introduction to the passengers, “You’re welcome to ask me any question except one…” A bit later later, “…and that one question is, ‘Why is the Georgetown Loop Railroad, Inc., leaving?'” Well, while professionalism might not allow him to do it, I certainly can bring you up to speed on what’s publicly known about how things got into this mess and where things stand today. While the mess has been hashed over and over again, I feel the need to drag the ugliness out one more time for the record, just so everybody remembers what’s been lost as they look at these pictures.

Fast forward to today, essentially 30 years after the start of reconstructing the loop. The current operator, Mr. Ashby’s original company, Georgetown Loop Railroad, Inc., has been in place for all thirty of those years, and has been as important in making the operation a success as the Colorado Historical Society. Last year alone, they provided service to over 115,000 tourists; this year, the rumored number is closer to 130,000. Contract negotiations broke down between the CHS and the GLR last spring over several points, but (as reported) primarily over significantly increased insurance coverage, turning over an unreasonably large percentage of profits to the CHS, and other shared maintenance expenses. Rather than working to resolve the differences, the CHS described their terms as non-negotiable, forcing the GLR to decline the contract offer.

With the GLR essentially forced to decline the contract offer, the CHS started the RFP (Request for Proposals) process in early June 2004, looking for a new operator for the Loop property. Since the CHS has taken down the document (makes sense, the process is over…), it’s mirrored over here at www.savethetrain.org for those interested in reading it. Of the four interested parties, only one actually bid – Railstar, Inc., of New York. Meanwhile, Mr. Mark Greska of the GLR has repeatedly and publicly stated they’re willing to pick up negotiations from where they left off, but the CHS has not responded. As of 30-Sep-2004, both Railstar and the CHS have signed the contract for next year, so Railstar it is. For those interested in their RFP response, it, too, is available from savethetrain.org here.

Railstar has no narrow gauge equipment. They’ve publicly stated that diesels may be running the Loop for the first few years – though I don’t know from where, since light, powerful 3 foot diesels are in precious short supply. With current trains running 7-9 cars, they’re either going to have to find something like the former USG units that the GLRR owns, or something comparable. As for cars, the CHS has apparently requested and received a bid from the C&TS to rebuild a couple of the old (read: non-used, boxcar-style) passenger coaches for Loop service. They also apparently purchased a couple freight car hulks at the recent Durango & Silverton auction. That’s all I know at the moment.

In the meanwhile, recognizing that Railstar can’t fulfill the RFP requirement of trains behind steam, the CHS has hauled C&S 9 (from the Loop grounds, but CHS property) and Colorado and Northwestern 30 (ex-Denver, Boulder and Western 30, ex-RGW 74, from Boulder, CO) out to Strasburg for inspection and possible rebuilding. Everything I’ve learned throughout this leads me to believe that the units are safe for the moment and in good hands at Strasburg. I’m told by many that Mr. Ulrich and the folks out at Strasburg are quite competent. Thus, should the money keep flowing, there’s a moderate chance either or (on a long shot) both will run again. At the very least, they at least care about the history and the machines, and most definitely have the knowledge to put them back together.

To their credit, the CHS has also publicly stated that no matter what, both units will be cosmetically restored, even if they can’t be made operational. We just need to hold the CHS’s proverbial feet to the fire if they fail to follow through on the cosmetic restoration commitment, lest 9 and 30 turn into two forgotten piles of rusting parts. Jim Poston has some photos posted here. Jim is also president of a group working to preserve the current sane state of the railroad – the Colorado Historic Railroad Preservation Association.

The Georgetown Loop equipment, being owned by the GLR, will be transferred mainly to museums for preservation. As I currently understand it, the motive power will go to the CRRM in Golden and the cars will be distributed amongst several locations, as the CRRM does not have space for them all.

Lest there be any confusion, I have nothing against Railstar. They’re absolutely in no way responsible for the hideously poor decisions on the part of the CHS that have lead us to this point over the past six months. I sincerely wish them the best possible luck in finding suitable equipment and rebuilding the Loop operation, both for the sake of the Loop itself and for the sake of the residents in Georgetown and Silver Plume.

Nor do I believe that the Colorado Historical Society should be disbanded. The fact that the Loop exists is a testament to what the CHS can accomplish when led by those concerned about history rather than some bizarre twisted agenda I don’t comprehend. All we need is to identify and ferret out whoever caused this mess and remove their power to ever do anything like it again. They CHS is partly an entity of the State of Colorado, and as Colorado residents (at least speaking for myself), we have a right and an obligation to try to correct that in our government which does not act appropriately. I can’t tell you who in the CHS caused this problem, nor why they’re doing what they are, but I can assure you that whatever goals they have, their actions indicate best interests of the Loop, the surrounding communities, and railroad preservation are not even on the list.

If you’re a Colorado resident or a railfan of any order, you should be mad as hell about what’s gone on here. I feel both sadness and anger every time I have to dredge this up, but it’s something that needs to be kept fresh in the mind of anybody interested in the Loop. It’s an example of the best interests of everyone being chucked out the door for some agenda not understood. We’ve lost one of the most popular, professional tourist railroads in the US. We’ve lost a fantastic steam program. Most importantly, though, we’ve lost the men and women, along with their devotion and knowledge, that spent 30 years building it to what it is today. Sunday, 3-Oct-2004, marked the final run of the Georgetown Loop with the great men, women, and machines of the GLR, Inc., and possibly the last time it will run under steam. It’s a sad and frustrating day for all of us.

Photographing the Morning Trains

The last time I was on the Georgetown Loop was back in the fall of 2002, when my wife and I were visiting my parents in Breckenridge. Of course that’s already in the trip reports section, oddly enough under my last Helper trip here. When it became undeniable that the last day the Georgetown Loop would be run by the GLR, there was only one option – buy a ticket (Photo #9) and get my rear up there for the final day.

I woke up a bit groggy Sunday morning, and stumbled out of bed, through the shower, through my office to grab the camera gear, and into the car. About ten miles from home I realized I’d forgotten to shut the garage door. So, nearly half an hour late, I was finally headed for Silver Plume. With a little luck, I’d still made it just in time to catch the first train being boarded and departing.

For a change, luck actually was with me. I pulled in just a hair before 1000h – about 0955h, I think. Just as I was getting off the freeway, Georgetown’s #14 was pulling up under the water tank. I grabbed a few shots out the window, but as usual, parking at Silver Plume was at an absolute premium. I wound up dropping the car roughly a couple hundred yards down the street from the station and walking in – quite briskly, I might add. The last time I was out, only the 2-8-0 #40 was up and running, so I was excited to see a Shay out and powered up.

The Georgetown Loop’s steam roster primarily consists of four units, Shays #8, #12 and #14, as well as Baldwin Consolidation #40. In addition, they also roster two GE diesels formerly from US Potash in New Mexico – #130 and #140. The most conventional of these units is probably Number 40, a three-foot gauge Baldwin 2-8-0 Consolidation built in 1920. The unit has an international heritage, although it was built in the US. It was originally built for the Guatemala International Railway of Central America (IRCA). In 1970, it came back home to the United States, where it worked on the Colorado Central narrow gauge tourist line until 1976. At that point, it was transferred over to the owners’ new project – the Georgetown Loop Railroad. Aside from a brief lease to the White Pass & Yukon Route between 1999 and 2002, it’s been on the Loop ever since.

For those not familiar with Shay-type locomotives, they’re a high tractive effort, low speed logging locomotive. Rather than a regular cylinder/rod arrangement, they have three pistons mounted vertically on the engineer’s side of the boiler. These then drive a horizontal crankshaft, which in turn drives other geared shafts that mesh with gears on the wheels. The result is a locomotive that can pull anything, anywhere – just not very quickly. They were very popular on logging and industrial railroads because of this fact – they would handle the heavy loads on poorly graded lines, and since speed wasn’t an issue, they were perfect! For those wanting to know more about these unique locomotives, might I suggest this site.

The GLRR’s three Shays are all oil-burning, 3-truck models built by Lima and thus very similar, but their heritage is somewhat different. #14 was actually the earliest built, in 1916, and is a 60-ton unit. Bearing serial number 2835, it was originally constructed for Norman B. Livermore & Company of San Francisco. Over the years it eventually would up at the West Side Lumber Company in Tuolumne, CA, before coming to the Loop in 1974 (and then disappearing for a while onto the rebuilt Colorado Central before coming back in 1980). #12 was built as serial 3302 in the spring of 1926 as a 60-ton unit for the Swayne Lumber Company of Oroville, CA, as their #6. Over the years, GLRR 12 went to the West Side Lumber Company in Tuolumne, CA, before winding up on the GLR in May of 1986. #8 is the big boy of the group, built as serial 3176 in March 1922 as a 70-ton Shay. It started out as Pickering Lumber #8, and eventually found its way to the Loop in 1977. As of Sunday, 3-Oct, both 12 and 14 were under steam, while 8 was tied down in a static display (Photos #11 and #12) by the Georgetown Loop Railroad offices in Georgetown.

I made the mistake of thinking that 14 would be leading the first train out of town that Sunday morning, but I realized I was wrong when I wandered up into the yard to find Shay #12 tied onto the front. So, no big deal, I figured – they’ll alternate off and on which unit would be used throughout the day. It would give those of us out to photograph the day’s trains (Photo #13) a little variety. The schedule board had the usual round of trains on it, but I learned that the reason they were firing up #40 (Photo was because of adding an alternating extra train to handle the large crowds showing up for the last operations.

So I proceeded to wander around the yard, photographing everything in sight, particularly the equipment, since it’ll all be off the property before the end of the year. It didn’t take long and Shay #12 was headed out of the yard, passenger train in tow, drifting down the 4.5 miles of track to Devil’s Gate. (Photo #15) (Don’t worry, the train was packed – I actually took the shot as the passengers were boarding, rather than waiting for departure.) What really surprised me was when Shay #14 promptly took off behind the passenger train. Not really having a good grasp on what they were doing yet, I decided the best course of action would be to get back in the car and photograph the first train headed down the hill. Plus I might also figure out what the heck that second Shay was up to…

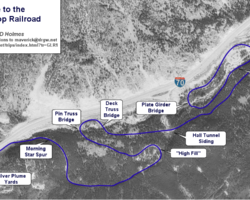

East of Silver Plume on I-70 is an overlook point where one can pull off the freeway and look out over the valley. As I pulled in, not only were there already a gaggle of fans there, but #12 was already pulling across the deck truss bridge and headed for the Hall Tunnel yard. That long walk back to the car had cost me a bit of time on the train, but since there’s really not much photography that can be easily done between the points, it wasn’t that big of a deal. Aside from a brief glimpse through the trees (Photo #16) as the train passed through the Hall yard (with the collection of other stored freight cars in the background), there wouldn’t be much in the way of opportunities until it hit the bridge. The best part was that the #14 was still just right behind it – Photo #17.

The problem with high mountain railfanning in Colorado is that the weather often turns ugly around noon, and nature wasn’t making an exception for today. Even at 1040h, as the first train was coming down across the high bridge, clouds were blocking the sun, making any shot not worth my while. However, as it rolled around the final curve and crossed Clear Creek for the last time on the plate girder bridge, it broke out into sunlight, making for an excellent overhead shot (Photo #18). While I’d half expected Shay #14 to have stopped at Hall Tunnel yard, it was still trailing along behind the passenger train. It was at that point that my cloudy little brain put the obvious together – they needed more power for climbing the hill, but didn’t want to double-head on the way down. The idea of seeing doubleheaded narrow gauge Shays was just about more excitement than I could handle, and it was so darn obvious. I don’t know why it didn’t come to me earlier, but that opportunity alone would make the entire day worth it.

Talking to some of the other fans at the overlook, I learned that they’d been doing this, along with running an alternating extra train, for the last couple weekends to accommodate the extremely high patronage. Today would certainly not be an exception – as #12 pulled in to Devil’s Gate station, we could all hear #40 and the extra whistle to leave Silver Plume. The only real siding on the line is at Hall Tunnel yard, which also conveniently seems to be about halfway time-wise. So as the scheduled train leaves Devil’s, the extra leaves Silver Plume, and vice-versa. Just as on a real railroad of the era, the scheduled train always has priority, and #40 would always be safely in the hole with the extra by the time the regular train showed for the meet. Sure enough, as #12 and #14 were backing under the high bridge with the 1055h train out of Devil’s, #40 was on its way down the hill.

The problem is that I wanted to photograph both – a double-headed Shay set rounding the curve definitely took priority, but I also wanted to catch 40 and the extra drifting down from the deck truss bridge. As it would happen, 40 came first so that it would be clear in the hole for the scheduled, and I caught it here at the west end of Hall Tunnel siding (Photo #19). Only a few seconds later, it was a matter of swinging the lens around and down to catch my doubleheader upbound and working hard as they crossed Clear Creek (Photo #20). By this point, while I was reviewing some of the shots I noticed that the camera was reporting a time a little past 1100h. I hadn’t realized it was so late already, and since I was riding the 1210h train out of Devil’s Gate, it occurred to me that I really should get down to Georgetown and collect my ticket.

Riding the Loop

One of the most interesting things to note is that the argument over the CHS’s behaviour is very public upon entering Georgetown. There are two banners over the main road – one from the CHS, promising the train will run in 2005, and another one that I’ve previously mentioned in Chapter 2 from CHRPA that simply says, “Show Us The Steam Train”. (Photo #7 back in Chapter 2) By now you know which one I believe more, but it’s still interesting that the dispute has spilled out into the public arena, hoping to convince those visiting the railroad.

Apparently everyone else for the 1210h train out of DG also thought it’d be a good idea to get their tickets at the same time I did, but despite the long lines, those of us with reservations were handled very quickly. It helps to have a great number of terminals and counter workers going – makes what looks like an impossible line go by very quickly. Many of those in line were either fans, like myself, that had come to capture the last day or locals that were out for one more ride on the Loop. The best was one guy ahead of me with his sons that was wondering if there were tickets left – they were just passing through, unaware this was the very last day. With luck, the woman behind the counter found them seats on the 1210h, as it wasn’t quite full. I was glad that they’d get the opportunity.

As a side note, all of the Georgetown Loop logo items in the GLR’s gift shop were marked half off, but unfortunately, being the last day, the selection was pretty picked over and I couldn’t find a darn thing I wanted. I would have liked a Loop hat, but no luck. It really was sad seeing the shop that barren. I remember being in there the last time I rode, and it was chock full of stuff. Seeing all the steamers up and running was one thing, but seeing the mostly-empty shop with closing sale signs everywhere was what really made the fact sink in (at least to me) that we were at the end.

After collecting my ticket, it was up to the Devils Gate parking area. I figured that being half an hour early would assure me a parking space, since the lot is usually packed to capacity. As luck would have it, I got one of the last few spaces up by the end of the high bridge. Fortunately del Sols are tiny little cars and fit just about anywhere – including in spaces others pass up as too short. As I was pulling in, 40 and the extra were just departing the station – I could see the plume rising as it was working upgrade just to the west. Lucky me – just in time to shoot it on the high bridge – along with the zillion other fans that were out. (Photo #21) Honest – this was the shot with the fewest stray heads in it.

The upside of digital photography is that I can put some 193 shots on a single run through my flash card. The downside is that I tend to blow through a lot of frames bracketing in hopes of a perfect shot and that when it does get full, it takes a while to unload. So, between the extra leaving and the scheduled train, I was sitting in my car, trying to offload as many shots as possible onto my laptop. I wanted to start out the run with a blank card, since I wouldn’t get another chance. Besides, I’ve always found shooting from a moving train to be a skill I don’t have, so again the policy is shoot a lot and hope one comes out okay. Usually I find my concept of vertical doesn’t agree with reality, and I come out with all sorts of cock-eyed photographs. Anyway, to make a long story short, by the time I got the laptop started and the photos dumped off, it made it just in the nick of time to catch 14 on the front of the eastbound regular train, crossing the viaduct at 1201h (Photo #22). Right behind it was #12 (Photo #23), meaning that we were in for yet another doubleheader up the hill (and thus probably a sold-out train). Then it was dump the card again, grab the extra batteries, and head down to the station for boarding.

I’ve ridden before, but these crowds were by far the largest I’d seen. Even when all the people from the 10:45 train got off, it still looked full – and we had a packed boarding platform worth of people just waiting to get on! I luckily found a seat on the north side of one of the open-air gons about halfway back in the train thanks to a seat opening up right in front of me. Just pure luck, but it would give me the best chance to photograph the trip up and back. Still, it would be tough, as the car was packed on both sides, crammed together to try to accomodate everybody that wanted to be out there. Even with the crowds, we were still running amazingly close to on time. The crew pulled us out of the station about 1215h, backed up to the end of the track to give everybody a view of the bridge, and then took off uphill with both Shays barking away on the front end. I really couldn’t have asked for more – two geared engines on the front and decent weather.

Ten minutes later, we were creeping across the viaduct, both to allow everybody time for photography, but also to allow time to appreciate the view. The view from 95 feet off the water is nothing short of incredible, but I have to say it was almost as interesting counting the number of railfans out and about. Once across the bridge, we quickly came back up to track speed, making our way towards Hall Tunnel.

Hall Tunnel is the site of a couple of spurs (including one down towards the Lebanon Mine – the mine that’s open for tours during parts of the year), and the only real siding on the line. At least the upper spur was still full of the GLR’s cars, and I presume the lower spur also had equipment stored on it. The GLR has so much historic equipment that it literally is just stashed in every available spot. It’s a wonderful collection. However, the siding was not full of stored cars, but rather ones full of revenue passengers. As expected, 40 and the extra train (Photo #26), headed downhill at this point, were safely tucked away in the hole waiting for us. Also out were numerous railfans, though I have no idea how they got here. Must have walked in from somewhere, but that’s one heck of a walk!

As our guide on the trip pointed out, one of the best shots on the trip is on the uphill run at the upper curve – the spot known as the high fill (because that’s just what it is – a large fill that holds up a curve). Usually the lighting and visibility of the power is good from this point, due to the sharpness of the turn and the relatively clear view across the inside of the curve. Also, the engineers make a point of sanding the flues at this point, leading to all manner of crap being ejected from the stacks. This provides a great shot of steam doing what steam does best – smoking. I was just a hair too far back in the train, as I never got a clean shot of both Shays, but the results in Photo #27 were still decent.

From the high fill, it’s only a short run on into the Silver Plume yards. The only thing in between is the Morningstar (or Morning Star) Spur, a short stub track just on the east side of the last curve before Silver Plume. For years, Colorado & Southern 9 sat here, rusting away. C&S 9 is a small 2-6-0 Cooke-built Mogul that was born in 1885 as Denver, South Park, and Pacific 72 (and later 114). It eventually became C&S 9, and was, at the end of its service life, exhibited at the 1939-1940 World’s Fair in New York. It briefly made another appearance at the Chicago Railroad Fair in 1948-1949 before being shut down for good and stored in Illinois. In 1957, it went to Hill City, South Dakota on the Black Hills Central, where it ran only briefly and then was left to deteriorate outside. The Colorado Historical Society purchased it in 1988, and moved it to the Morningstar Spur, where it again sat in the elements. The tragedy of all of this is that 9 is the last surviving example of its class of South Park locomotives. Of the 8 the South Park had (and the 14 that the C&S inherited down the line), this is the only one that was not cut up. The unit is now out at Strasburg, CO, to have its asbestos insulation removed and then to be as a possible rebuilding candidate to run the Loop in a year or two. Only time will tell, but it may be one of the few positives that comes out of this debacle – for the first time, 9 is starting to receive serious care and preservation work.

As I mentioned, Morningstar is only a stone’s throw from Silver Plume. Just a minute after passing where 9 used to sit, we were coming off the grade and into the yards (Photo #28). From there, it was a quick run around with engine 12, and once again 14 would follow us down the hill to help haul the next regular up. Since I’m sure you’re sick of listening to me ramble at this point, I’ll just leave you with photos of the return trip. I hope you’ve enjoyed this trip report, no matter how grim parts of it might be. The larger picture might be both sad and maddening, but I have to say this was, hands down, one of the most fun days I’ve ever had out on a tourist line. Where else in 2004 can you see three working narrow gauge steamers, including two geared locos doubleheading up a steep grade in some of the best scenery Colorado has to offer? All I ask is remember why we’ve lost this priceless experience, and who and what brought us to this point. Enjoy the rest of the photos.

All photographs in this trip report were taken with a Canon EOS 10D with a Canon 28-105mm USM, a Canon 100-300mm USM, or a Canon 75-300mm f4-5.3 IS/USM.

This work is copyright 2024 by Nathan D. Holmes, but all text and images are licensed and reusable under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. Basically you’re welcome to use any of this as long as it’s not for commercial purposes, you credit me as the source, and you share any derivative works under the same license. I’d encourage others to consider similar licenses for their works.