Some Context – A Brief History of the Silverton Branch

With the battle with the Santa Fe over the Royal Gorge and Raton behind them in 1879, investors started to again provide funding for General Palmer’s D&RG. The first thing the road did in 1880 was start construction on three large expansions towards sources of new revenue – a feeder west from the Royal Gorge area to the mines of Leadville, CO, a feeder south towards Santa Fe, NM, and a long branch westward towards the San Juan mountains and whatever riches might be there. Call it railroad prospecting if you will – Palmer was sending feeders out in any direction that had the potential to turn up new traffic. The last of these branches, from the end of track at Alamosa to the San Juans, would appropriately be known as the San Juan Extension.

Being a narrow gauge route, and a bit of a gamble at that, the line was poorly graded and had a good number of sharp curves, but proceeded quickly westward across Cumbres Pass and then towards the San Juan area following various canyons. Completed for operation in August 1881, only a year and a few months after starting the extension, almost perfectly 200 miles of track were strung across the wilderness towards the small town of Animas City, near the southern base of the San Juan mountains. Animas City, while interested in being a railroad hub, declined to meet Palmer’s demands of free land for the railroad facilities. True to Palmer’s style, the railroad then decided to actually build their facilities at a new town just south of Animas City, calling this new terminal Durango. Within a few years, the population attracted by the prosperity of the region settled in Durango, relegating Animas City to virtually unknown status. Durango, however, promised little revenue compared with what lay only 45 miles to the north – the high mountain country and the emerging silver and gold mining industries around Silverton.

Silverton is a small town high in the San Juan mountains (just over 9300 feet!) that started its existence in 1860 with Charles Baker’s discovery of gold in the area. However, it wasn’t until the 1873 treaty with the local Native American tribe, the Utes, opened the whole area to settlement. Even then, being in the high mountains without any easy route to market, large-scale mining wasn’t yet practical. However, a wagon road in opened in 1879 provided some access, and prospectors quickly realized the potential held by the area – not in the gold originally sought by Baker, but primarily in silver, hence the town’s name.

Eager to tap this revenue, the Rio Grande built the Silverton Branch – 45 miles of track – in only nine months. This is really quite incredible, considering the rockwork that needed to be done in order to pass through the lower Animas River canyon (along what today is called the High Line). Parts of this construction cost nearly $1000/foot, a notable sum when railroad cars were a few hundred each and a new locomotive was only around $4500. By July 1882 the line was complete, and mining in the area boomed. At one point, over forty mines operated in the hills above town, shipping both their products and their supplies over the Rio Grande and three small feeder railroads that connected Silverton to the mines. Thousands of tons of ore flowed south from Silverton to the American Smelting and Refining smelter at Durango, located south across the river from the roundhouse. Supplies for the mines and miners flowed north by the trainload. Those supplies coming in, and the refined metals going out both flowed over the San Juan Extension to reach the rest of the US railroad network. Business was good, at least for a while.

By 1890, under pressure from mining interests and debtors seeking an inflationary panacea to their problems, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was signed into law, which obligated the government to buy 281,250 pounds of silver every month at market rates, and established that currency could be redeemed for either gold or silver (the US was taken off a bimetal gold/silver standard in 1875). Instantly silver doubled in value with the new demand coming online and consuming nearly the entire silver output for the country. It didn’t stay at that price, though, but continued to drop as silver production continued to increase. Because of this, in the end the plan backfired because the dropping silver prices instilling fear with investors, particularly foreign ones, that the value of a dollar would drop significantly due to the greater percentage of less-valuable silver backing the currency than gold. This eventually lead to the Silver Panic of 1893. Pointing to the Sherman Act and silver as the primary cause, Presiden Grover Cleveland and the Congress immediately immediately repealed the act in mid-1893. The silver mining industry crashed, having overextended itself during the three boom years and now being stuck with the price of silver plummetting back to below its pre-1890 levels. This event marked the end of the silver booms across the American West, and with it much of the mining traffic from Silverton.

By 1895, metal prices had started to rebound, and many of the mines at Silverton had found gold ore in sufficient quantities to remain viable. In 1897, some half of the output of Silverton’s mines was gold, with the rest being lead, zinc, silver and copper. The big boom started with a huge gold strike at the Sunnyside Mine in 1899, and subsequent nearby strikes. While actually somewhat north of Silverton, the town was the established base for commerce in the area and still at the head of the only link to the outside world – the D&RG. After 1910, though, many of the mines played out or were closed due to environmental problems (flooding, washouts, mudslides, avalanches, etc.) Before World War I, there was a brief increase in zinc mining, but even this lasted only a short time. The Silverton Branch’s glory years for freight traffic were quickly fading.

As time went on and the mining activities decreased, agriculture and timber became the dominant commodities. These, however, largely did not move over the Silverton branch. In 1905, the Farmington Branch was constructed south from Durango to the ranching and farming areas around its namesake Farmington, NM. (As a historical note, it was constructed as standard gauge, then converted to narrow gauge in 1921 when it was clear the San Juan Extension would never be converted to standard gauge.) The Pagosa branch was responsible for much of the lumber that moved over the route. The Silverton branch, once the moneymaker of the route, was slowly slipping towards insignificance. By the 1940s, World War II brought a little relief to most of the San Juan Extension from a temporary increase in mining – not for silver or gold this time, but for copper, zinc, and uranium. When the war ended and freight traffic returned to virtually non-existant levels, abandonment of the Durango-Silverton segment became a real possibility.

By 1951, the whole of the San Juan extension was in danger as well, with traffic down to a trickle, replaced largely by new highways into the region. Even the Rio Grande was shifting freight traffic from the narrow gauge to Rio Grande Motorways, its rubber-tired subsidiary. On 1-Feb-1951, passenger service on the line from Alamosa to Durango ended with the demise of the line’s through passenger service, the San Juan. In 1952, Durango’s other railroad connection to the outside world, the Rio Grande Southern (running up the west side of the San Juans to Ridgway and the D&RGW connection), was scrapped. In the midst of it all, though, the regular train between Durango and Silverton, appropriately enough called The Silverton, was on the rebound. Through a general rise in tourism after WWII (made possible in part by the very highways killing the narrow gauge), careful marketing by the D&RGW, and its appearance in several Hollywood movies, tourist ridership on the Silverton train began to rebound, in stark contrast to the rest of the narrow gauge system.

Things weren’t quite over for the San Juan Extension, however. The line received a reprieve from the scrapper in the 50s from an oil and gas boom near Farmington. This led to solid unit trains of pipe transported over the route, in addition to drilling supplies. However, by 1960 even this traffic had largely dried up, with the oil wells and pipelines being completed. By 1966, only 20 trains plied the Antonito-Durango line during the entire year, and by 1967 the abandonment paperwork was filed. The last revenue freights ran at the very end of August 1968, with the last westward run over the line being 5/6-Dec-1968, powered by 473 and 483 and with Engineer Andy Payne, Fireman Robin Yates, Conductor Jim Mayer, and Brakemen John Nolan and Denny Cummins. With that, the era of narrow gauge freight in Colorado came to a close.

Scrapping started at Chama and working west on 20-Sep-1970, and by a year later, nearly the entire line was pulled up. The only sections saved were the Silverton branch, thanks to its profitable tourist business, a 64 mile segment over Cumbres Pass sold to the states of Colorado and New Mexico (now the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic), and the dual gauge (then converted to standard gauge) line from Alamosa to the perlite mine at Antonito.

Today, the Silverton Branch continues as the only section that has had continuous passenger service for its entire history (some 123 years). In 1967, the line itself became recognized as a National Historic Landmark. The route continued to be operated by the Rio Grande as Subdivision 12-B of the Alamosa or Colorado Divisions until 1981. At that point, Charles Bradshaw, Jr., purchased the branch to further its potential as a tourist attraction under the current name, the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. In 1989, the line was again sold to American Heritage Railways, who continues to operate it to this day.

Saturday, Feb 26, 2005 – The First D&S Winter Photo Special

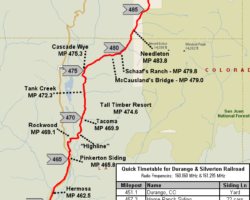

For the past fifteen years, the Durango & Silverton Railroad has been holding annual Fall Photographers’ Specials. This year, they decided to see just how many of us crazy people would wander out in the cold and snow to participate. The idea was to allow both railroad and photography enthusiasts the chance to photograph the train running through pristine winter environment on the remote, inaccessible parts of the line – mainly between Rockwood and Schaaf’s Cabin, about four miles north of the Cascade wye. As it turns out, at $79/person, about 86 of us hearty (or crazy) individuals decided to participate, out of the ceiling of 100 they had space for on the run.

At 0800h on Saturday, Feb 26, 2005, we departed Durango for points north on a train consisting of K-28 #473, a boxcar, three coaches, two open-air cars, and a caboose. While it was relatively cold, the day started off completely clear and sunny. Over the course of the day, we did numerous pre-staged photo runbys at locations such as just above Tacoma, at the Tall Timber Resort, at the old Cascade siding, at the Cascade wye (both of our photo special and of the normal winter train turning around), and then up at the McCausland Bridge and at Schaaf’s Ranch. Obviously, with the open air gondolas and the curvature of the branch, a great number of additional photo opportunities presented themselves as we rolled along as well.

Most of the passengers had the good sense to use the warm coaches and their reserved seats to warm up between photo runs, but yours truly spent the whole day freezing in the rear gon. I don’t regret it one bit – it’s the most fun I’ve had in a long time, and hopefully you’ll enjoy the photos. The entire trip was absolutely first rate. My hat goes off to the folks of the Durango and Silverton for an absolutely exceptional run on Saturday – thanks for all the effort invested into putting together this event. You all are what makes the D&S worth coming back to over and over again.

Durango Yard Tour – Saturday Evening, Feb 26, 2005

On the way back, it eventually began to snow, but then by Durango we were back out in clear skies and sun again. Right around 1800h we pulled into the Durango depot. Afterwards, the D&S employees were generous enough to treat us all to a tour inside the roundhouse and machine shop. In what might be considered an act of heresy amongst steam enthusiasts, I asked about the diesels. I’ve photographed every piece of steam the D&S has to offer, but I hadn’t ever seen any of the diesels yet. One of the D&S employees guiding us around (I believe his name was Mac, but I could have that wrong – should have taken notes) offered to escort a few of us to the rear of the yards where all that good stuff lives – such as the old rolling stock, the back of the roundhouse, and, of course, the new diesel fleet. (See Chapter 3 for shop/yard photos)

Following the San Juan Extension – Sunday, Feb 27, 2005

With Saturday done and no regular train running on that Sunday, I clearly had to find something else railroad-related to do on the way home. Sitting in the hotel the night before, I realized that no discussion of either of Colorado’s two longest remaining narrow gauge railroads (the Durango & Silverton and the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic, of course…) is complete without a discussion of the original railroad line that created them – the Rio Grande’s famous San Juan Extension. Now nearly forty years after the last revenue D&RGW train ran over the line, a surprising amount remains, hidden in the valleys of southwest Colorado and northewestern New Mexico. Since I was already out that far, I decided to use most of Sunday coming back to drive along the old right of way, checking for surviving artifacts from the old route. In the last part of the trip report, we’ll cover all but a few miles of the route between Durango, CO, and Chama, NM.

All photographs in this trip report were taken with a Canon EOS 10D using either a Canon 28-105mm USM or a Canon 75-300mm f4-5.3 IS/USM.

This work is copyright 2024 by Nathan D. Holmes, but all text and images are licensed and reusable under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. Basically you’re welcome to use any of this as long as it’s not for commercial purposes, you credit me as the source, and you share any derivative works under the same license. I’d encourage others to consider similar licenses for their works.