Southwestern Railroad

In late March of 2004, I had the opportunity to meet up with a small part of my family (my parents, an aunt/uncle from Illinois snowbirding in Tucson, and an aunt/uncle from Victorville, CA) in Tucson, AZ, for a couple days. Looking forward to getting out the Colorado cold, I figured there was always time to squeeze in a couple days of railfanning on the trip. What better way to take a mini-vacation – family, two copper-hauling shortlines along the route (the Southwestern RR in New Mexico and the Copper Basin in Arizona), and five days of warm weather on open roads with my convertible. I needed a break from work anyway, so on Thursday night, 25-Mar-2004, I set off southbound for Albuquerque that night, then on to Silver City, NM, the next to meet up with my parents for dinner. It just so happens that the first stop along the route on Friday would be the Southwestern Railroad, covering its length between Rincon, where I got off I-25 southbound, and Silver City, where I was headed for the evening.

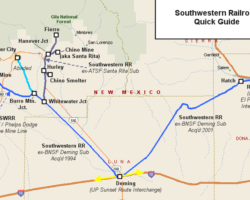

The Southwestern Railroad actually consists of three pieces, two of which are adjacent segments out of Deming, NM, and the other the far-off Shattuck Branch out of its namesake town in Oklahoma. I’ve got the Shattuck Branch queued up for an upcoming Texas trip report, but here we’ll be looking at the two copper hauling pieces – the original SWRR from Peruhill, NM (just west of Deming), up to the copper mining regions around Silver City, NM; and the former ATSF, former BNSF Deming Subdivision from the El Paso Sub connection at Rincon, NM, over to Deming and to the original SWRR route at Peruhill.

The Southwestern Railroad got its start on 15-Jun-1990, when it acquired the entire Silver City cluster of lines down to Whitewater Junction, where the western forks (Silver City and Tyrone) met up with the Santa Rita Sub (the line from Whitewater to Santa Rita, via Hurley). (As a note, 15-Jun-1990 is also when the SWRR acquired the Shattuck Sub in OK/TX.) Almost exactly four years later, on 12-Jun-1994, the Southwestern acquired everything from Whitewater back down to Peruhill, just five miles from Deming. Finally, on 8-Sep-2001, the Southwestern acquired the rest of the Deming Subdivision as a way to continue New Mexico operations in the face of falling copper prices and closing mines.

An Overview of the Southwestern’s Routes Today

The NM

routes now run by the SWRR have a rather long, twisting, and complex

history, but are fairly simple to understand as they exist today.

Rincon marks the east end of the line, where the SWRR interchanges with

the BNSF on their El Paso Sub. The line proceeds southwast-ward to

Deming, NM, where the SWRR interchanges with the Union Pacific.

Continuing northwest, the line runs from Deming up to Whitewater, where

the branches start to split out into copper country.

The right fork, going northeast and formerly known as the ATSF Santa Rita Sub, heads up to the SWRR’s yard and offices in the former-ATSF depot at Hurley. From Hurley, a large yard goes towards the Chino smelter (owned by Chino Mining, a joint Phelps Dodge – Heisei Minerals company, and formerly Kennecott), and the line continues north through Bayard to Hanover Jct. At Hanover, one fork goes right / eastward towards towards the former town of Santa Rita, now the Phelps Dodge Chino copper mine, once a large source of traffic on the SWRR. The other fork from Hanover continues northward to Fierro, which has little traffic in the SWRR era.

As previously mentioned, the former Santa Rita Sub mainly exists today to serve the Chino Mine. The Chino Mine – the large open pit mine above Bayard – was originally started around 1800, and was worked intermittantly (mainly between Apache attacks on settlements and miners) until the late 1890s, when the richer veins were worked out (rich in those days was >10 percent copper concentrations). With new concentration methods developed that were able to deal with the lower-grade sulfide ores (<2.8 percent copper), the Chino Copper Company was founded in 1909 and modern strip mining began in earnest. Somewhere along the line, Chino Copper became a partnership, with two-thirds owned by mining giant Phelps Dodge, and one third by Heisei Minerals. By the time operations were suspended in 2002, over two billion tons of rock had been extracted from the mine, with an average copper concentration of around 10 pounds / ton.

Also served on the former Santa Rita line is the only smelting and refining complex on the route. Hurley, in addition to being the home of the Southwestern Railroad, is also home to Chino Copper’s refining complex. Based on what I’ve read, it would appear that higher grade sulfide ore at the Chino Mine was crushed on site and had the copper ore separated out by floatation. This sulfide ore slurry was then sent to the Hurley smelter via pipeline, where it was smelted down into reasonably pure copper. Hurley also has a more modern extraction facility, though, in the form of a solvent extraction – electrowinning (SX/EW) process. For SX/EW to work, large piles of low-grade ore are treated with a sulfuric acid solution that leaches out the copper. This solution is then fed into an electrochemical cell, where the copper in the mixture is essentially plated onto what starts as a thin, pure copper electrode. By the time the process completes, a very pure copper electrode weighing hundreds of pounds is produced. While the Hurley smelter itself was shut down in 2002, the SX/EW plant is apparently still running at reduced capacity.

Getting back to the modern SWRR system, the left or west fork at Whitewater goes over to Burro Mtn Jct., where the line to the Phelps Dodge Tyrone Mine splits off to the left. Formerly, the other fork from Burro Mountain went to Silver City, but I don’t think this line is still intact much beyond Burro Mtn. Junction. The Tyrone Branch, however, is the only large source of traffic in the Silver City route cluster, as it’s the only remaining active mine. Founded in 1921, it too is a large open pit mine, but other than that I can’t find much information about it.

The western end of today’s Southwestern, from Deming to the furthest reaches at Fierro, the Chino Mine, and the Tyrone Mine, is completely dependent on the mining industry for traffic. With both the Chino Mine and Smelter shut down, the western end is hurting, and in places looking more like a railroad graveyard than an active line. Still, the Tyrone Mine provides some traffic, and the offices are still located in the former ATSF depot at Hurley. The east end is a bit less mining related, and I’m guessing most of its earnings come from car storage and interchange, as well as adding a longer haul for stuff coming from the BNSF headed for the west end of the route.

Historical Background – Before the SWRR

Now that you’re

probably confused enough by the modern state of the route, let’s go back

before the SWRR and take a look at the history of the many routes that

came together to build it. The Deming Subdivision – the route from

Rincon to Deming – was constructed by the Santa Fe-affliated Rio Grande,

Mexico and Pacific Railroad in 1881. It was an extension of the New

Mexico and Santa Fe Railroad’s southward route from the CO-NM line

(Raton Pass) and Albuquerque, and in fact part of a larger effort to

complete the second so-called transcontinental railroad by

connecting with the Southern Pacific. Obviously this transcontinental

was second to the original UP-CP route via Utah, completed in 1867.

(Also, just as a note of accuracy, neither were truly transcontinental

but only semi-transcontinental.) As a note, all of these companies were

subsidiaries or affiliates of the main Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe

railroad, and were in fact absorbed into their parent in 1899.

The SP had really gotten the town of Deming off the ground with the arrival of what’s known today as the Sunset Route from Los Angeles in Nov 1880. In fact, the town even owes its name to the SP, as it’s attributed to Charles Crocker’s wife’s maiden name (CC was one of the Big Four, and an executive of the SP). In the true tradition of transcontinental building, officials drove a silver spike to mark the RGM&P’s arrival and the route’s completion in Deming on 7-Mar-1881. Not all was well, however, and the SP refused to develop joint rates or route much traffic via the new ATSF connection. The SP, rather, wanted to complete its own route east, and thus continued building the Sunset Route east of Deming towards El Paso, TX, and New Orleans, LA. Thus, the Santa Fe’s first transcontinental attempt was relegated to little more than a stub in the desert that interchanged some modicum of traffic with the SP.

In an effort to make some use of their investment, the ATSF conglomerate negotiated trackage rights over the SP Sunset Route as far west as Benson, AZ. From there, yet another ATSF subsidiary, the New Mexico & Arizona Railroad, built a connection to Nogales, Mexico, in 1882. This, too, proved to be a business failure, and in 1897 the Benson-Nogales line was sold to SP, to be at least partially operated until 1962, when it was completely removed.

Not all was lost, though. The Lake Valley branch, starting from Nutt, a high point on the Deming Sub about halfway between Rincon and Deming, reached the Lake Valley Mine in 1884. This mine, by pure luck, hit the richest silver deposit in New Mexican history, extracting ore that yielded 16,000 ounces of silver per ton, as opposed to the usual of 70 oz/ton. By its closure, it had produced in the neighborhood of 2.5 million ounces of silver. The twelve mile branch was abandoned, however, once the boom ended.

Another project started in 1882, the Silver City, Deming, & Pacific, was to be the line’s success story and eventual salvation. With the burgeoning electrical industry, the demand for copper in the 1880s was quite high. While the silver boom that started Silver City, NM, in 1870 had long since played out, there was significant potential for further mining, especially of copper ore, in the area. Original built as a 3ft. narrow gauge, the SCD&P completed the 48 miles of trackage to Silver City on 11-May-1883. The folley of narrow gauge was soon realized, however, and on 16-May-1886, the road was switched to standard gauge operations to better integrate with the Santa Fe system. By 1891, business was booming, and the Silver City & Northern started the 21 mile branch that would eventually extend from Whitewater Jct. to Fierro (by 1899). This is the modern-day line that now passes through Hurley and up to Hanover Junction. The small four mile chunk between Hanover and Santa Rita was built by the Santa Rita Railroad in 1897. All of these – the SCD&P, the SC&N, and the SRRR – were all merged into the ATSF proper around the turn of the century in 1899 and 1900.

The final fork of today’s system, the branch to Tyrone from Burro Mountain Jct, was actually built by the El Paso and Southwestern as an isolated stub. It’s important to remember that the EPSW was essentially a part of the Phelps Dodge mining company, and was started as a way of hauling ore from their mines to their smelters. It later expanded into a way to reach other railroads for better rates, and finally became a railroad in and of itself, but still vitally tied to the mining company that spawned it. Having built up from their southern mainline at Hermanasas to Deming in 1901 in order to connect with the Santa Fe for shorter hauls and better rates to eastern points, it was only logical to construct the Tyrone branch in 1921 to service the Phelps Dodge Tyrone mine. The branch was isolated, however, with EPSW trains running over ATSF track between Deming and Burro Mountain Jct. This was only shortly before the end came, however, and the falling price of copper forced PD to sell the entire 1200 mile EPSW system to SP in 1922.

Chasing One on the East End

One of the things that attacted

me to the SWRR is its unique roster containing a good number of GP30s,

all inherited from Phelps Dodge. Upon arriving at Rincon a little after

noon on Friday, 26-Mar-2004, I found SWRR 3000 (a GP40 of unknown

heritage) and SWRR 28 (one of the ex-PD GP30s) working the interchange

yard with BNSF. As is just my luck, the GP30 would be trailing on the

westward trip, if they were indeed going west again and not just tying

down. Since it didn’t look like they’d be done any time soon, I went on

into Hatch to search for some lunch, which turned out to be an

incredibly good burrito, and fuel for the trip west to Silver City.

After hearing a bit of unintelligable chatter on the scanner (stay tuned to 160.380 MHz – that covers the whole SWRR), I headed back over to Rincon to check on the local. To reach the south side of the yard, take NM Road 154 west out of Hatch. Right as the road comes to the the junction with NM 140 and turns left across the track to the north side, go rather straight instead and you’ll wind up on a road that goes a short way along the south side. It took me a bit to figure that one out, since I’d come in from the east end of Rincon and couldn’t find a grade crossing. Sure enough, the whole thing was reassembled at the western yard throat, and aside from the conductor that was down “watering the trestle”, everything looked ready for departure. At this point, the train was SWRR 3000, SWRR 28, and seven empties – a tank car, a center-beam flat, four grain hoppers, and a boxcar on the end. (Photo #2) You have to admit, even more than forty years after it was built (June 1963), SWRR 28 (ex-Phelps Dodge 28) is still looking good as a revenue-earning locomotive. You have to love that GP30 profile. (Photo #3) Right around 1330h, they were off, headed westbound towards Deming.

Immediately west of Rincon, the line crosses over the Rio Grande. Not the railroad, but rather its namesake river. My parents, who had also been travelling towards Phoenix via west Texas, had mentioned in passing that the Grande was running extremely full. Sure enough, though you can’t see it in the photo, the mighty river is right up towards the top of the piers under the bridge. Photo #4 shows SWRR 3000 leading across the three truss span Rio Grande bridge at MP 1082.9.

West of the Rio Grande, the only major town before Deming, some 50-odd miles west, is Hatch. Hatch’s main claim to fame are its world reknown chiles – it even has an annual Hatch Chile Festival around Labor Day. As far as the railroad goes, there’s not a whole lot here. There’s an old elevator off to the north side of the track, and a team track beside a concrete loading dock on the south side. The loading dock makes for a nice shot of afternoon westbounds, though (Photo #5). West of town, the road (NM 26) and the railway split and are separated by several miles, so this is a good last shot before you launch off into the high desert.

The next paved access to the line that I found was some 18 rail miles west of Hatch, about halfway between the stations of Hockett and Nutt. Hockett may or may not be accessible, but I believe it to be inside a large dairy farming operation, so I didn’t really try. The road I picked was local road A030 (Cristian Road) south of NM 26, which crosses the line at grade. There are large dirt parking areas on the south side of the crossing, and you’ll put these to good use if you’re chasing a train from Hatch (read on). The shots both east and west are good, and locals were friendly, even if curious as to why on earth a guy in a black convertible was sitting by their crossing pointing a large camera down the line. It seemed to take a small eternity for 3000 to arrive, though. I could see its headlight back at what I presumed was Hockett, but it didn’t seem to be making any progress. After almost an hour (thank goodness I put a book in the car, for times just like this), we finally got a train working up the grade. (Photo #6) At first I thought they’d picked up a few cars at Hockett. Really, they’d just rearranged things a bit. Note that the tank car is now buried in the train (even though it’s empty, and whatever it was carrying before may have very well been harmless), rather than next to the locomotives. Just past the grade crossing, it looks like the climb to Nutt and beyond gets started in earnest, but in reality, I think the climb probably starts several miles back. (Photo #7)

The next accessible point after this is Nutt, where the former Lake Valley branch used to split off. Part of the grade is still visible today, but the trackage is long gone. As you’re driving from east to west, it also looks like a summit – but it’s not. It’s only a false summit, an illusion to those unfamiliar with the route. In all honesty, the road and railway will continue climbing most of the way into Deming. (Photo #8) That’s not to say that the SWRR wastes any time through this stretch. Getting ahead of them is still easy with 65 mph speed limits, but it doesn’t take all that long for a train to catch up.

Between Nutt and Mirage, the tracks follow the highway perfectly through the high, dry, barren desert landscape. There are quite a few small arroyos crossed on small trestles, both wooden and steel, but very little else of scenic interest. The one exception to that is an old steel water tank and some stock pens before Mirage. The light was horrible, however, so I didn’t stop for a shot. Up closer to the actual summit just short of Mirage, though, the scenery begins to change from high desert to a more rocky, rolling terrain. (Photo #10) Mirage itself is the last siding before Deming, and at the moment seems to be used for generating per diem car storage revenue. It has the notable distinction of being one of the few grade crossings you’ll encounter between Nutt and Deming, which makes for an easy last grab shot of any westbound. I even got mine with the first direct sunlight I’d seen in an hour. (Photo #11)

From there, it’s mostly downhill to Deming, with the line breaking away from the highway and without any way to access the line until the Deming yard proper. When I arrived, there were a large number of UP employees around the yard (this is right on the Sunset Route, don’t forget), along with an equal number of conspicuous No Trespassing signs. So, I decided not to dally about the yard, but rather gassed up again and headed up towards Silver City and the rest of the SWRR.

The Arizona Eastern Railway

There’s not much I have to say on this one, since I didnt’ find anything running. The AZER runs from the copper mine near Miami, AZ, down to the interchange with the Union Pacific at Bowie, AZ. It’s another former SP branch that was spun off.

Copper Basin Railway

About equal distances north from Tucson and east from Phoenix lies an area rich with copper mining history, and with it, copper mining railroads. It’s in this basin, centered around Hayden, AZ, that one of the most interesting little short lines in the Southwest exists – the Copper Basin Railway. Connecting with two other copper roads that are mostly shut down, it has weathered the depression of copper prices far better. It acts as both a common carrier and mine-to-smelter plant railroad for ASARCO, and all very much alive on a daily basis. Since it forms a vital link between the mine at Ray and the smelter at Hayden, the eastern part of the system sees a virtually continuous heavy ore shuttle operate back and forth. It’s also railfan-friendly, powered exclusively by either first generation diesels or GP39s, bears a unique grey and metallic copper paint scheme, and is one of the dynamic success stories of US shortline railroading.

Brief History of the Ray Complex and Copper Basin Rwy

Copper mining in the basin east of the Phoenix area first started in the

mid-1800s, mostly, as I understand it, along the Gila River near the

ghost towns of Cochran and Buttes. The area around what would become

Ray was identified early on as a source of copper, silver, gold, and

other minerals, but it wasn’t until 1882 that the Ray Copper Company was

set up in order to begin extraction. Ray itself didn’t come into

existance until 1909, when large scale extraction from underground

(shaft) mining began. The Hayden facilities were built a year or so

later, aroudn 1910-1911, to process the output of the Ray Mine. By

1933, Kennecott Copper bought out the local company, and in 1948 they

began converting the operation into a modern open pit copper mine. In

1986, ASARCO (the American Smelting and Refining Corporation) bought the

whole works, and began a series of modernizations on the mine, the

concentrator, and the smelter that give us the Ray Complex we see today.

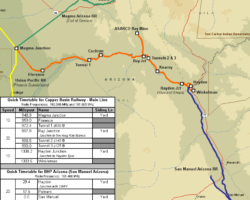

Obviously any mining endeavor of this scale requires railroad support, and the Ray/Hayden area is no exception. The Phoenix and Eastern Railroad arrived on the scene in 1903, having completed its line to Winkelman, just south of modern day Hayden. The P&E eventually folded into the Southern Pacific by the 1920s. The mine lead from Ray Junction up to the Ray Mine, as well as the plant railway leading from Hayden Junction to Hayden, were all built by the copper companies to support their operations and were privately owned during the SP era. The Copper Basin came on the scene in 1986, in parallel with the ASARCO purchase of the mining works and smelter. The CBRY assumed operations of the SP branch from the mainline at Magma Junction to the end of track at Winkelman, as well as the two ex-Kennecott Copper lines (Ray and Hayden). Thus, the CBRY became not only a common carrier, but also one that operates an essentially inter-plant mining railroad.

The Copper Basin operations focus around a unit train that runs between the concentrator loadout at the Ray Mine and the dumper at Hayden. The loadout is deep within the mining works, but can be seen from the visitor’s overlook on the west side, high above. This unit train, usually having roughly 60 100-ton ore hoppers, operates five complete trips a day between the two points, some thirty miles each way. The train bears the symbol OT-1 (presumably Ore Train 1) on its southbound / loaded trip, and OT-2 on its empty return voyage. These trains are regular as clockwork, and make for some very easy railfanning (aside from the fact that they move right along, wasting no time). The railroad also hauls other products for the operation on various locals to and from the UP interchange, but I wasn’t able to nail down the schedule on those.

If you come on CBRY territory, there’s at least one name you should know – Lowell “Jake” Jacobson, an ex-UP man that retired from the class 1 in the early 1980s. Jake is now COO of the Copper Basin, and, by every account I’ve read, runs a tight ship with a very dedicated group of employees, loyal because of his unique personality, his devotion to the company and employees, and his excellent management style. Almost certainly in part because of him, the CBRY has the distinction of being very friendly towards safe, responsible fans. Apparently if you stop by the office, they’re usually happy to give you a couple spare minutes to have you sign a release and give you an idea of what will be moving about the system. For those wanting to know more, and there is a great deal more than I can fit in here, I’d suggest Steve Schmollinger’s articles in both the October 2001 issue of Trains (Who is Jake Jacobson…, pp. 51-57) and the August 2002 issue of Railfan & Railroad (Railfanning the Copper Basin Railway, pp. 39-43).

Monday on the Copper Basin

Having spent Saturday night and Sunday with my family in Tucson, Monday meant starting the return trip to Colorado Springs, CO. It wasn’t a terribly long drive, done directly (only about 12 hours), but top on my agenda for the day was to explore the San Manuel Arizona (if it was running), the Copper Basin Railway, and possibly what remained of the Magma Arizona if I had time. After waking up late and taking nearly an hour to pick my way from near the Tucson airport up to clear running on AZ Hwy 77 north (heavy morning traffic), I showed up in San Manuel around 1130h on the wayup to the Copper Basin.

San Manuel used to be the site of a large BHP copper mining and smelting operation. It had two pieces to its rail system – the common carrier San Manuel Arizona line that operated between the junction with the Copper Basin near Winkelman and the smelter at San Manuel, and the mine railroad that ran from the smelter up the hill to the mine itself. However, in June of 1999, the railway was shut down due to both the mine and the smelter being closed on account of low copper prices. Today I believe it’s operated as the BHP Arizona railroad, carrying a few cars in an out every week on what is, by all accounts, a rather erratic schedule. The upside, however, is that the line travels over several spectacular trestles near the south end, as well as a large steel trestle over the Gila River near the CBRY interchange. With the road being on the east side, morning is the right time to shoot the SMA.

With my arrival in San Manuel, I stopped to take the top off the car, get something to drink, and pick up new batteries for the scanner, since mine had died the previous night. I found the rails up to the mine well rusted over, as one would expect after five years of shutdown. I also spotted three geeps in SMA paint sitting deep inside the smelter complex. Being too far away to shoot the power, and seeing no sign of anything moving any time soon, I wrote off the SMA and headed up towards Hayden and the Copper Basin Railway.

It’s rather funny how things work out. The first thing that caught my eye coming into Hayden was a Copper Basin ore train unloading beside the highway. I pulled over to have a look at it, and when I was walking back to the car I noticed something moving out of the corner of my eye. As I looked over towards the high bridge across the Gila, I noticed a small blue and yellow geep dragging a small handful of cars behind it. By the time I got a longer telephoto slapped on the camera and targetting on our new-found train, it was unfortunately off the bridge. Still, the shot of SMA GP38-2 18 was better than I expected, given that I thought they only had three motors, and I’d seen three at San Manuel. (Photo #32)

My initial plan was to follow one of the empty ore trains up to the Ray mine, and then continue onward towards home. Based on that, I thought it best to drive up through Hayden proper while the ore train was still unloading, just to see the town and look around for anything moving near the smelter. Unlike the other smelting operations we’ve seen from this trip, ASARCO’s plant in Hayden is still fully operational. Copper prices have been rising again lately after the massive drop from 1998-2002. Since ASARCO never shut down the Ray operation, there’s not the cost barrier of bringing an idled mine / smelter back on line. A good part of the plant is on the backside of this small hill, and thus can’t be seen, but the concentrator and the stack are both clearly visible from the town. (Photo #33) One interesting piece of the railroad’s heritage can be seen from the town streets, however – back within the Hayden complex’s yard, a 2-axle GE industrial critter motor can be seen. (Photo #34) I don’t think it’s been used any time recently, but it’s an interesting locomotive type you don’t see very often.

Concentrated ore is unloaded by the southbound OT-1 trains down along AZ Highway 177. The unloader is hard to miss, and as I mentioned, there was one in the unloader when I arrived. The crew dumps about half the train (30 cars, for 60 ore hoppers total), cuts off the power (Photo #35), runs around and pushes the rest of the train through the dumper. This is done because the dumper siding is actually too short, and after about 30 cars the crew has the power on the switch needed for the runaround. The ore is carried up to the smelting plant via a conveyer that runs from the dumper, over the road, and up to the plant high above. The train, meanwhile, once unloaded becomes OT-2 and is ready to proceed north to the mine. Thus, the whole process starts over, for a loop that repeats about five times a day, I’m told. When times were better, I’ve read that two unit ore trains ran continuously, each with around 48 cars.

I’d planned to stop in the office (located at Hayden Jct – Photo #36) while waiting for the unload to finish, but after my trip through Hayden, I found that the ore train was nowhere to be seen. A note to other visitors: the unload process is darn quick, so if you see one unloading, wandering off probably isn’t a good idea. That sudden sinking feeling that my scenic sidetrip had made me miss yet another train was starting to set in, but as I rounded the curve northbound into Hayden Junction, I saw the last few ore jennies of OT-2 disappear around the curve ahead. That saved the day, since I wouldn’t have time to wait for another full cycle – I still had nearly a thousand miles to get home.

From Hayden to nearly Kearny, the line runs on the west side of Hwy 177, with very few grade crossings. The only public one seems to be Tristan Road, about a mile or so south of Kearny. There’s also, of course, the Tilbury Road crossing in the town of Kearny, if Tristan doesn’t work out. However, by the time I’d reached Tristan, I was a minute or so ahead of the OT-2 (aka CBRY 401 north). With the sun overhead and slightly off to the west, I pulled off on the west side of the crossing onto a small dirt area and got out to set up the shot. Within minutes, CBRY 401, one of the few GP39s with a nose Gyralight, came around the corner, nose light on. (Photo #37) For those interested in unique freight cars, like myself, I’ve also included a photo of one of the CBRY’s unique ore jennies passing by as Photo #38.

The CBRY’s roster, as mentioned earlier, largely consists of GP39/GP39-2s. CBRY 401, 402, and 403 are natives of this operation, having been purchased for the Ray Mine operation as GP39s Kennecott 1, 2 in June of 1970 and GP39-2 Kennecott 3 in December 1980. CBRY 501 and 502 are ex-Kennecott GP39-2s from Utah (KCRR 591 and 596, respectively), and have rather strange looks due to originally having the high Kennecott cabs, now cut down to normal size. The other three GP39s – CBRY 503, 504, and 505 – are ex-C&O units (3912, 3901, and 3916, respectively), built in July of 1969 and rebuilt by Paducah before coming to the CBRY. The roster is rounded off by an equal number (8) of chop-nosed first generation geeps. CBRY 201 and 202 are GP18m units of Rock Island heritage (1239 and 1238); 203 is also Rock Island but a GP9 (1329). The other five (CBRY 204-208) are all GP9s from BN predecessor roads (BN 1704 / NP 204, BN 1822 / GN 670, BN 1867 / NP 244, BN 1893 / NP 276, and BN 1959 / CBQ 274). (Thanks to the Loconotes mailing list, Bob Lehmuth, and Jake Jacobson for those bits.) While I was there, the GP39s were most all on the job, while the first generation power was mostly stored at the road’s shops at Hayden Jct.

Kearny, the next town north along the route, is the result of the Ray Mine pit growth. The miners used to mostly live at a town called Sonora, but as the Ray pit expanded, Kearny was constructed in 1958 to relocate them. Eventually, as the pit grew, the townsite of Sonora was swallowed up and no longer exists. As a note for fans, it’s simply impossible to make it from Tristan Road, after waiting for the whole train to go by, to the Tilbury crossing in downtown Kearny ahead of the train. They just move too darn fast, and it’s not enough distance. Save your Kearny shots for the southbounds – it’ll work better anway.

Ray Junction can be accessed in two ways – one from the south, one from the north. As a fan, you’re actually looking for signs pointing to Kelvin, the actual town that exists to the northwest of the junction. Coming down from the north, the road is right on the northeast side of where the Ray Branch grade crosses AZ 177 at grade. It’s paved down just beyond Kelvin. Ray Junction can be found by following the dirt road that turns left over the Ray Branch at the south end of Kelvin. Coming up 177 from the south, there will be a sign pointing left to Kelvin approximately 3.2 miles north of Kearny. It’s a dirt road that will wander down towards Tunnels 2 and 3 (though you can’t directly see either of them). Eventually you’ll wander out at the same place – Kelvin.

Don’t waste too much time, though. Following the speed limit (and in a low-clearance car like my Del Sol, that’s usually advisable on dirt backroads), you won’t make it into Ray Jct. much ahead of the train – a few minutes at most. Just before the junction yard, you’ll find a curve with a very nice trestle shot, which is just north of Tunnel 2. (Photo #39) From there, it’s only a mile or two west to Kelvin and the curve that brings the Ray branch up and out of the Ray Jct. yard. The mainline is following the water-level Gila River grade at this point, whereas the Ray Mine is high above and to the north. The branch has quite a grade to it in order to make the connection, but fortunately it’s all downhill for OT-1, the loaded ore trains. Only the empties have to work their way uphill, at the Ray Block speed limit of 10 mph. Because of the low speed through the yard as well, you’ll have no trouble getting ahead of an OT-2 for another shot. With the sun nearly overhead still, I chose to be on the west side of the branch, actually in the town of Kelvin. There’s a good paved road on the west side of the line, allowing for shots of trains coming up through the curve. (Photo #40)

Past Kelvin, the paved road follows the branch back as far as the Hwy 177 grade crossing. With the trains only moving at 10, there are a couple of breaks in the embankments and desert scrub that allow another shot or two. As a last look at an OT-2 before it enters mine property (the other side of the 177 grade crossing), we see CBRY 401 beneath the signature saguaro cacti of Arizona, just a mile or so north of Kelvin. From there, the OT-2 will cross Hwy 177 and disappear into the mine for about an hour to load up on concentrated ore. After that, it’s back to Hayden as OT-1.

On the far west side of the pit, accessed from Hwy 177 as it heads up the mountains towards Superior, is a visitor’s overlook that can be used to watch operations in the pit. The Ray Mine pit is an incredibly massive hole in the ground (Photo #42), and the second largest copper mine in Arizona. Owned by ASARCO, Inc., miners blast and haul an astronomical amount of rock to the concentrator every day. The concentrator strips the copper sulfides – the useful ore for smelting – from the waste rock and presumably copper oxide ores (which are electrolytically refined), producing some 26,000 tons per day. The result of this process is a rock-like substance that’s 20-30% copper and thus economically feasable to haul down to the Hayden smelter by rail. Five times a day, sixty 100-ton cars of an empty OT-1 train are pulled up the Ray branch to load out. From the visitor’s area, the loadout siding can be clearly seen off to the far right (and down! – Photo #43).

From the point at which we left OT-1 in Chapter 3 (just short of Hwy 177), it took some 45 minutes to get into the mine loop. By this point, the crew had already run around the train and had the power on the south/downbound end of the train, and then backed slowly into the loadout. The train was loaded from the first car behind the locomotives to the end, and then after some delay (presumably a good solid brake check), a call went out over the radio announcing the start of another OT-2 and its return trip through the Ray block. The Copper Basin uses 160.545 MHz and 161.505 MHz, and it’s extremely helpful to monitor those frequencies. My observation is that ore trains tend to be quite chatty, especially when MoW people are out and about. I basically sat at the overlook until the ore train had loaded, and then climbed back into the car and awaited a call on the radio. A few minutes later, the call came and I was off down the hill again. I hadn’t really intended to chase it back, but the light was so darn good and I was having so much fun, I figured why not photograph the loaded run as well.

My advice is that, as you follow an ore train up or down, contemplate the photographic possibilities of a train going the other way. Unlike most shortlines, a train going the opposite direction isn’t hours or days away – with an hour or two, you’ll get the reciprical unit ore train running. It’s not an if, it’s a when. Just such a thought came into my mind about Kelvin. The Ray branch makes a long draw down through town before curving sharply east to join the mainline. The paved road, if you continue south, crosses the Gila and climbs swiftly up into the mountains. From one of these hills, an long shot down across town and up the brach would be very possible. I even drove up, parked, and started to walk up to the top of the hill when I looked through the lens. Because temperatures were nearly 90 and the winds were fairly calm, the air was still, but riddled with heat distortions. Such a long shot wasn’t going to work out well in the end. Plus I hate rattlesnakes, and out there seemed like a perfect place to stir one up.

I plopped back down in the car and headed down the hill to Kelvin, looking east rather than west as I passed over the grade crossing. There, back in the trees, sat a train that wasn’t there an hour or so before. It’s a protected crossing, and while I usually check both ways for safety reasons anyway, I just hadn’t noticed the idling motors a few minutes before. Apparently a local had been following the OT-1 I was chasing, and had tied down just past Ray Junction. It had the usual three motor set – all GP39 variants, including both ex-Kennecott Utah units (501 and 502, with their odd cabs), spliced by what must have been 504. I grabbed a few shots of 502 basking in the afternoon desert sun (Photo #44), and then proceeded back up to the Ray Junction Road grade crossing for a shot of OT-2.

The loads roll down the branch at the same crawling speed that the empties roll up to the mine – 10mph – probably because of the grades, weight, and track structure involved. It gives you plenty of time from the point you hear the rumble and the horns for the crossings north of Kelvin to the point you actually have to make the shot work. Even then, between shots, there’s plenty of time. Here we see OT-2 both approaching the Ray Block sign (and speed limit marker), with mine tailings piles and mountains in the back (Photo #45). A minute later, OT-2 is over the Old Ray Road crossing (which leads down to the yard, as we saw with the chase of OT-1 earlier) and rounding the corner down to join with the mainline. (Photo #46)

I could have followed the 25mph Old Ray dirt road back out to AZ 177, but I opted to return up along the Ray Branch on pavement instead, and hit the road for Kearny. While I was in Kearny on the trip down to Tucson, I’d seen a shot that would work particularly well for an evening westbound, and the sun was now low enough in the western sky to make it work. As you approach Kearny from the north, you’ll see a sign for Tilbury Road. Turn west onto it, and follow it around down towards the railway. Navigational note: you’ll need to nearly turn right to follow the road as it meets Bristol Road at the bottom of the hill. Once you’re across the tracks, hang a right (north) up to the park. Get out of your car, and walk over towards the track. You’ll see a sweeping curve with a backdrop of cliffs, tailings, and the desert mountainscape. It just so happens that a loaded OT-2 finishes off the shot perfectly, as CBRY 503 and crew prove. (Photo #47)

Just as you can’t get from the grade crossing where I shot OT-1 the first time to Kearny, you can’t do the reverse, either. So, I decided to head back to Hayden Junction, since the light was very strongly from the west. With the highway on the east side of the line, western light doesn’t work well unless you can cross the track somehow. Besides, for the most part, the line and the highway are separated by a good distance down to Hayden Jct. anyway.

Between Hayden Jct. and the ore dumper is a short (less than 2 mile) section of track with a steep grade – close to two percent. For a loaded ore train with only three four-axle geeps, it makes for one thunderous show of EMD power. Just to the east/south of Hayden Jct., the line to the smelter crosses the road. On the west side of the highway, there’s a large dirt pullout where one can stay safely away from both traffic and trains, but still watch the whole show. Really it would work better in the morning light, but even in the afternoon it’s a sight to behold – three GP39s pulling their guts out and filling the air with blue-grey EMD exhaust haze. Twenty-two minutes after passing the grade crossing at Kearny, OT-2 had reached the west end of the Hayden Jct. Yard and was starting into the climb. (Photo #48) If you wait a few minutes, there’s also a great shot of the train climbing towards the unloader, with the grade making the power appear above the tail end. (Photo #49)

At 1750h, the train was about halfway through the unloader. (Photo #50) The crew was about to cut off the power and run around, beginning the process of once again becoming OT-1. Exactly 4 hours and 30 minutes after my arrival, the unit train had come full circle, and the endless cycle between the mine and the smelter was about to repeat (Photo #51). It was actually longer than I’d anticipated staying, but it’d been a very good day. From there, I made a quick turn back to up Ray Junction to check on the local, which still hadn’t moved. If it had, I briefly had considered following it. As it was, though, the other half of the line – the section from Ray Junction to Magma Junction (Photo #51) – would just have to wait for the next trip.

All photographs in this trip report were taken with a Canon EOS 10D with a Canon 28-105mm USM, a Canon 100-300mm USM, or a Canon 75-300mm f4-5.3 IS/USM.

This work is copyright 2024 by Nathan D. Holmes, but all text and images are licensed and reusable under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. Basically you’re welcome to use any of this as long as it’s not for commercial purposes, you credit me as the source, and you share any derivative works under the same license. I’d encourage others to consider similar licenses for their works.